Schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic trematodes of the genus Schistosoma, remains one of the most widespread neglected tropical diseases across Africa, Asia, South America, and parts of the Middle East. While human behavior, socioeconomic conditions, and public health infrastructure all influence disease transmission, environmental factors are among the most decisive forces shaping the distribution, intensity, and persistence of schistosomiasis worldwide. Understanding how ecological, climatic, and water-related conditions contribute to the life cycle of the parasite is essential for designing effective control strategies.

The Schistosoma Life Cycle and Environmental Dependence

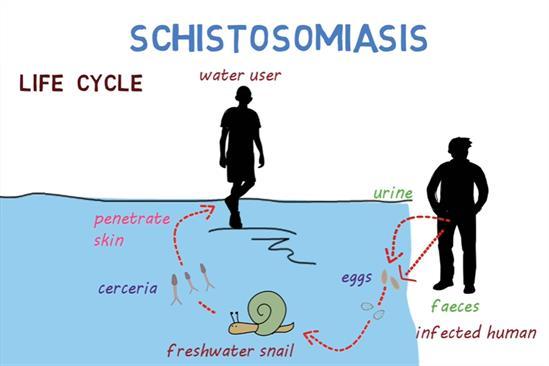

The spread of schistosomiasis is inseparable from the ecological requirements of the parasite and its intermediate snail host. The life cycle begins when eggs are excreted in human urine or feces and reach freshwater sources. Once in water, the eggs hatch into miracidia, which must quickly find and penetrate specific freshwater snail species. Inside the snail, the parasite develops and multiplies, producing free-swimming cercariae that are eventually released back into the water. These cercariae infect humans by penetrating the skin during contact with contaminated water.

Each stage of this cycle is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, meaning that ecology directly governs where, when, and how effectively transmission occurs.

1. Water Availability and Irrigation Systems

One of the strongest environmental drivers of schistosomiasis is the presence of slow-moving or stagnant freshwater that supports snail proliferation. Natural water bodies lakes, marshes, and rivers with low flow have long been associated with high transmission rates. However, human modifications to the landscape have accelerated the problem.

Dams and Water Projects

Large dam projects such as the Aswan High Dam in Egypt created ideal snail habitats by reducing water flow and expanding irrigation networks. These shifts altered ecosystems in a way that increased Schistosoma transmission despite the economic benefits of the dams.

Agricultural Irrigation

Irrigation canals, rice paddies, and man-made reservoirs provide warm, shallow water conditions that snails thrive in. Workers often have repeated contact with these waters, making agricultural communities disproportionately affected.

Thus, water infrastructure both natural and engineered plays a central role in expanding or limiting schistosomiasis transmission.

2. Climate and Seasonal Variation

Temperature, rainfall, and humidity strongly influence both snail populations and parasite development.

Temperature

Snails and Schistosoma larvae flourish within specific temperature ranges. Warmer water speeds up snail reproduction and the parasite’s maturation inside the snail. Climate models suggest that warming temperatures in some regions may expand the geographical range of transmission, pushing schistosomiasis into previously unaffected areas.

Rainfall Patterns

Rainfall determines the availability and quality of freshwater habitats:

-

Heavy rainfall can wash away snails and reduce infection risk.

-

Light, consistent rainfall creates more stable habitats ideal for snail survival.

-

Dry seasons force people to use fewer water sources, sometimes increasing exposure to contaminated sites.

These seasonal fluctuations mean that infection risks can vary dramatically throughout the year.

3. Water Pollution and Ecosystem Disruption

Changes in water quality affect snail hosts and parasite survival.

Organic Pollution

Domestic waste, agricultural runoff, and nutrient-rich sewage can increase snail populations by boosting algae and aquatic vegetation, which snails feed on.

Chemical Pollution

Some pollutants, such as pesticides and industrial chemicals, can reduce snail populations, but they can also harm natural snail predators. When ecological balance is disrupted, snail hosts may rebound even more quickly than before.

The complex interplay of pollutants, biodiversity, and habitat stability makes it clear that ecosystem health is directly tied to schistosomiasis transmission levels.

4. Biodiversity Loss and Predator Decline

Healthy aquatic ecosystems contain predators crustaceans, fish, ducks that naturally limit snail populations. Biodiversity loss due to overfishing, pollution, wetland destruction, or invasive species removes these natural controls.

For example, in some areas where snail-eating crayfish were depleted, snail densities surged, leading to increased transmission. Conversely, reintroducing native predators has shown promise as a sustainable ecological control strategy.

5. Human Behaviors Shaped by Environment

Environmental factors also influence human water-contact patterns. Communities located near lakes or rivers often rely on these bodies for bathing, washing, fishing, and recreation. In agricultural areas, farming activities require daily water exposure. When safe water infrastructure is lacking, people may have no choice but to enter potentially contaminated waters.

Urbanization trends may mitigate risk when clean piped water becomes available, but urban expansion can also create polluted, stagnant water habitats that harbor snails.

Thus, environmental context shapes human behavior, which in turn shapes exposure risk.

6. Climate Change and Future Risks

As climate change reshapes global ecosystems, schistosomiasis patterns are expected to shift. Rising temperatures, altered rainfall cycles, and increased extreme weather events could create new habitats for snails or disrupt existing ones. Some regions may experience declining schistosomiasis rates, while others may see rapid expansion.

Predictive modeling suggests that environmentally driven redistribution of risk may require public-health systems to prepare for emerging hotspots.

7. Integrating Environmental Management into Disease Control

Traditional schistosomiasis control strategies rely heavily on preventive chemotherapy using praziquantel. While drug treatment is essential, it does not prevent reinfection. Environmental management is therefore crucial.

Effective strategies include:

-

Snail control through biological or environmental means (e.g., vegetation removal, reintroducing snail predators)

-

Improved water and sanitation infrastructure

-

Designing irrigation systems that limit snail habitat formation

-

Educating communities about seasonal risk patterns

-

Monitoring environmental change to anticipate transmission shifts

In some countries, discussions about access to antiparasitic medications such as the availability of treatments for other helminth infections including options like mebendazole Australia pharmacies provide highlight broader public-health concerns about equitable access to essential medicines. Although mebendazole does not treat schistosomiasis, its mention underscores how the distribution of antiparasitic drugs often intersects with environmental and socioeconomic determinants of disease burden.

Conclusion

The spread of Schistosoma infections is profoundly shaped by environmental conditions. Water availability, climate, ecological balance, and human-driven environmental modifications all contribute to the creation of habitats in which snails and parasites thrive. As global climate patterns shift and human development continues to reshape landscapes, understanding these environmental drivers becomes increasingly important. Only by integrating ecological insights with medical and public-health interventions can long-term, sustainable control of schistosomiasis be achieved.